What's in a name?

Just your average freakout about bestowing a name on your child

A couple months ago, a popular formula brand sent me an email with the subject line: “21 weeks: How to decide on a baby name.” Apparently, we had passed the threshold at which it was unacceptable to have no idea about names. The tips are actually not insane, suggesting brainstorming, researching meanings, considering popularity, and thinking about the middle name. Besides the fact that I would never put a name on the list without first checking the Social Security Administration register of births in the last five years, I have found that these types of straightforward pieces of advice do nothing for me. It’s not that it’s difficult to curate a list of aesthetically-pleasing names that aren’t in the top 500 most-common names in the 2020s, it’s that the act of naming a human is so freighted with meaning I balk at the task.

The fact that both my husband and I loathe our names—no one is naming their kids Lindsay and Kevin these days, and I’d say for good reason—is certainly a factor in my hesitation. Growing up with a sister who had a cool name (Charlotte has hovered between 3rd and 4th most popular name for female births since 2020), I longed to feel that my name matched me.

When I was 15, I wrote in my journal that I’d decided to change my name to Maitland in college. “I don’t like Lindsay that much and Maitland is at least original. That’ll be good. So there ya have it. I will be Maitland Hunt. MAITLAND HUNT.” Lol.

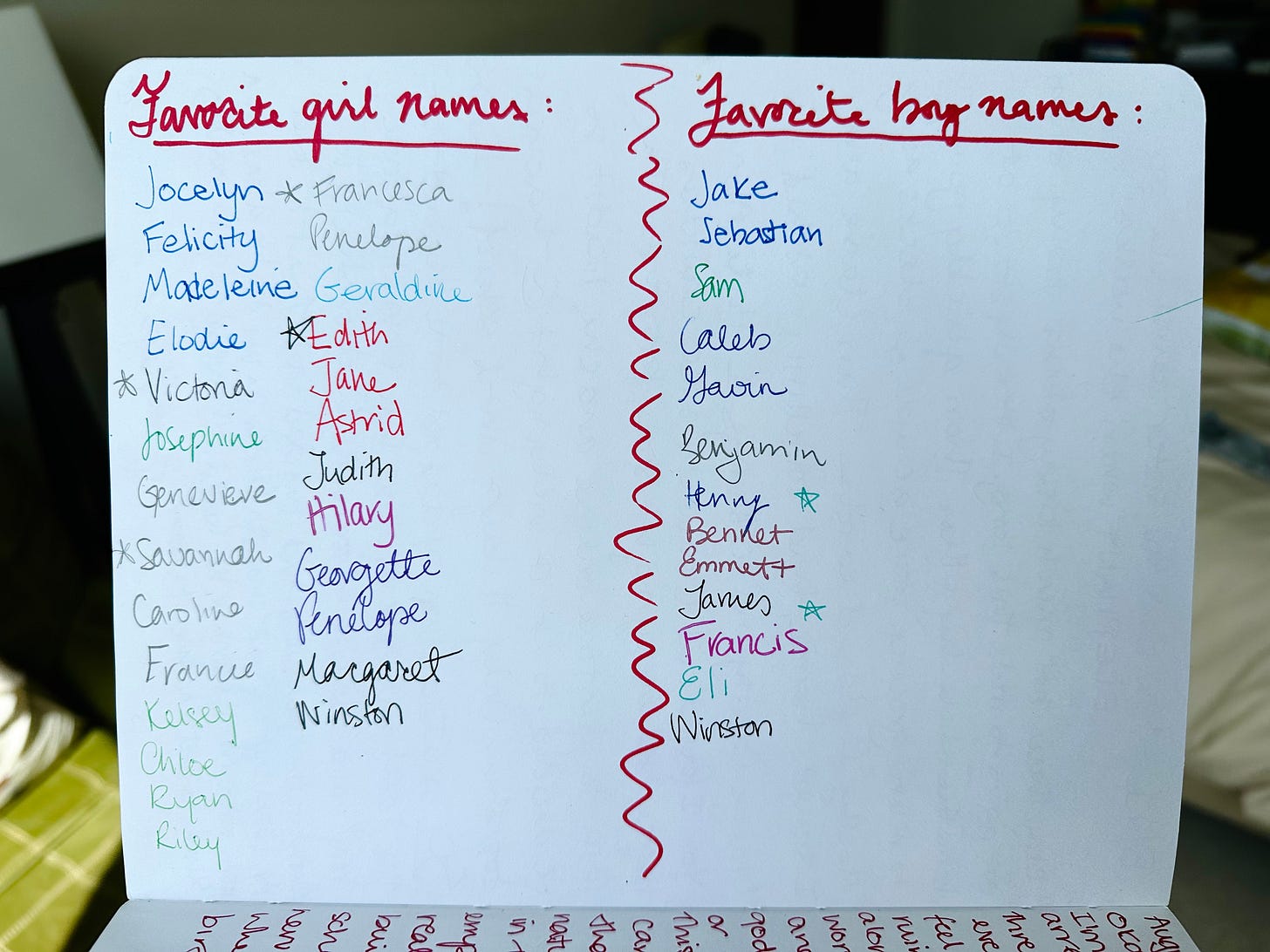

A few pages later in the same journal, I made a list of favorite girl and boy names. The names are in different inks, so I assume I returned to the page over the course of the journal, adding names that I liked. Notable entires include my adding both my parents names (in the same pen, so I’m thinking they were added in a rare moment of teenage parental appreciation) and that both lists end with the name Winston.

Looking at the list 22 years later from the perspective of semi-imminent parenthood, it seems both strange and obvious that I thought it was worth documenting different names. I wasn’t thinking about eventually having a baby, but instead recognizing that names are an aesthetic exercise in figuring out one’s identity.

It is no different now: choosing our child’s name is an social exercise in identity performance. What is perhaps odder, though, as we winnow our list down to the final ONE is that it is my husband’s and my identities selecting a moniker for a being that will be different and separate from us.

If there’s one thing that Kevin and I have heard consistently from friends who are already parents, it’s that the kid comes out with its personality and essence intact. Yes, this is anecdata, but time and time again, our friends say that their child was already and always who they were. (Two friends have told me they knew their babies’ personalities in the womb.) The point they are trying to make is that that the historical emphasis on nurture is wrong: these babies’ personalities are literally nature incarnate.

In The Gene, by Siddhartha Mukherjee, he explores a similar thread. Behaviorist approaches to personality saw it as something molded by the environment. How you acted as parents, in other words, determined your child’s personality. However, in identical twin experiments, personality came to be understood as something that was determined genetically. Since identical twins share the same DNA, being reared apart in different environments would help reveal what was nature and what nurture. I have loved reading this book, and reading the section about this research made me gasp aloud and read the entire thing to Kevin. Quirks that seem totally original were shared across twins that had never met. For instance, one set of male twins was raised an ocean apart: One, as Jewish in Trinidad, the other as Catholic in Germany. But they both had the same habit of flushing the toilet twice every time they used the bathroom—once before and once after using it. WHAT IN THE HELL? Mukherjee gives more examples to underscore the point that genes influence personality. However, the debate between nature and nurture becomes murkier when you consider epigenetics, or how environmental factors act on gene expression.1 While we all possess genes that could create a certain outcome, it is various factors—chance, or fate, if you will—that determine their expression. This allows for differences in identical twins. How I think of it is: our genes create potential, our environment enacts it.

So the little kicking gremlin inside me is going to come out with a genetic personality potential—the first derivative of personality, as Mukherjee calls it—and her name is a major environmental factor that we are bringing to the table. Emily Oster concludes in her small roundup of name-related research that “simpler names are perceived more favorably,” with LinkedIn chiming in that apparently CEOs have shorter names. So if you are looking to press your child into the service of capitalism ASAP, I suppose take your advice from a corporate social media platform and go for a one-syllable, three-letter name. Meet our CEO baby: Dee, Rae, Kit, Nat, Ann.

What this does make me think, as we ponder the impossibility of selecting a name, is that it is both obvious that a name influences how you perceived and the difficulty in knowing or interpreting such perception. I think of my dad cautioning us not to choose something weird and the branding exercise that naming a child has become in influencer circles. The name we select is inevitably a derivative of Kevin’s and my expressed genes, which in turn become a lever for her own genetic blooming. Though we can control the name but we cannot control the outcome.

This morning, Kevin and I laid in bed longer than usual and discussed names. He teased me for trying to create alliterative first and middle name pairs for our top contenders. One first name felt more right than others. We spoke it aloud, letting the name hover between us. Was it her? Could it match to the writhing being in my belly? We will see.

I titled this essay with the oft-quoted phrase from Juliet’s soliloquy: “What’s in a name? That which we call a rose / By any other name would smell as sweet.” This is often interpreted as Shakespeare’s saying that a name does not determine a thing’s essence. However, as Juliet and Romeo are fated to find out, their names do have mortal consequences. I’m not saying our little baby is going to get into some sort of double-suicide love pact because we call her Calliope and not Lillian (neither are on the list to be clear), but there’s more to a name and identity than we might think.

There’s much more to say on names and identity, but I’ll leave things here for now. Please share your naming anxieties with me! And suggestions for baby names very welcome.

Mukherjee notes that there is some disagreement about the meaning of epigenetics, in many cases used to describe heritable changes to a genome, versus how it’s used here, which is the way the environment acts on gene expression.

Love this, thank you for sharing your thoughts! I loved your bit about LinkedIn tips for CEOs, so I can do the exact opposite haha. As I am in my third trimester, we've been noodling on names for a while and are down to a top three, after many conversations about how to balance unique, but not TOO unique. My thinking is I don't want to give him a name until we see him, but my fear is what if I just don't know which name is supposed to be his?! Especially if I'm sleep-deprived and exhausted... that just doesn't feel like a great time to make a big decision that can impact the trajectory of someone's life.

Love this!